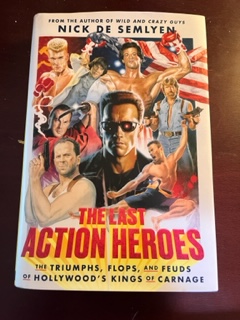

Nick De Semlyen, the editor of movie magazine Empire, recently published a film history book with a very clear title, The Last Action Heroes: the Triumphs, Flops, and Feuds of Hollywood’s Kings of Carnage. De Semlyen’s book focuses on eight of Hollywood’s major action stars of the eighties and nineties: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Chuck Norris, Dolph Lundgren, Jackie Chan, Bruce Willis, and Steven Seagal.

De Semlyen’s writing is professional, research-heavy, and readable. The author never makes his overview of this period in Hollywood history about him. He never even mentions what led him to write the book. The back of the book includes thirty pages of citations and the depth of research and thought is palpable in this thoughtful, intelligent, and fun book.

The Last Action Heroes doesn’t seem to set out to put any of these performers on a pedestal or take them down either. De Semlyen recognizes the discipline that most of these movie stars share – Stallone waking up at 4 or 5 am every morning both before and during his stardom to work out, Schwarzenegger’s decision to cut ties with his Austrian parents when he moved to California to pursue his career, Van Damme finding someone to take care of his dog when he left Belgium for the United States – while also pointing out their many flaws, both self-acknowledged and alleged by others. Even the star the author seems to warm to the least, the famously arrogant Seagal, is illuminated through anecdotes that illustrate his capacity for generosity and diplomacy.

De Semlyen probably could have included more consideration on how these stars’ films, with their hardcore violence, might normalize or even promote violence in the real-world. Then again, one of the book’s strengths is that it is a very clear work of journalism rather than cultural criticism. He does mention Norris’s decision to make less violent television shows and movies, Willis’s complaints about always carrying a gun in his projects, and Stallone’s eventual turn towards very public and brave anti-gun, pro-gun control stances.

This is a fun and immensely readable book.